11: Mary Oliver & Extraordinary Teaching

I made structural changes in my class four weeks ago. Here's how it's going.

Welcome to Field Reports!

Every two weeks, I share insights and updates from my classroom, reflecting on my pedagogical practices.

For creative writing and ELA activities to use in your class, check out Plug & Play!

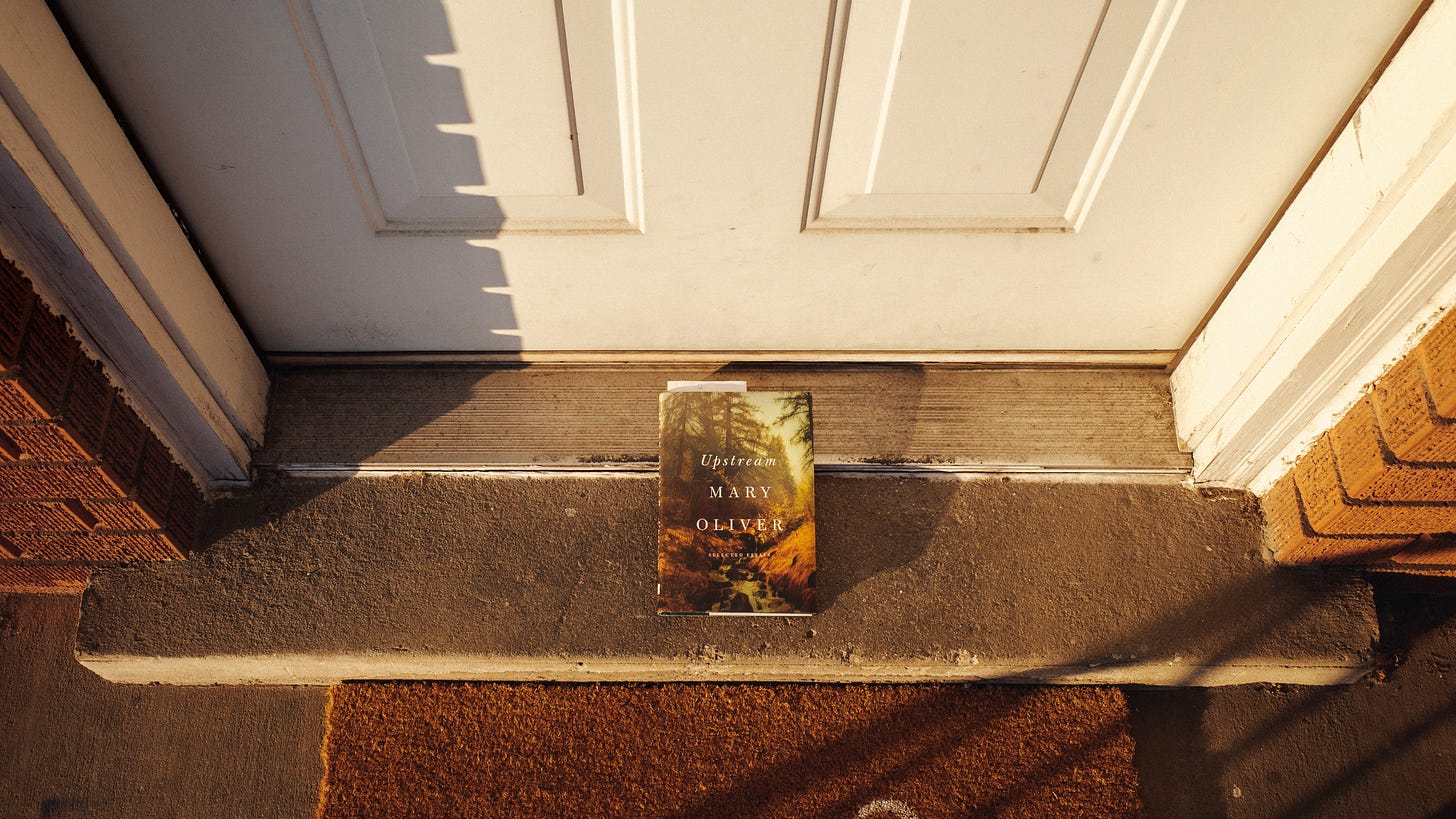

You know you are blessed with a good neighbor when they surprise you with a book on your doorstep to borrow—especially when the book is accompanied by a note guiding you to their favorite parts.

Neighbor: you know who you are. Thank you. ◡̈

In my last field report, I talked about structural changes I made in my classes. There’s been some good, and there’s been some bad, and I’ll get to that, but first: we begin with Mary Oliver.

Mary Oliver

In her essay “Of Power and Time,” Mary Oliver says she is simultaneously, “three selves at least.” First, there is the child she once was—“powerful, egotistical, insinuating” whose presence “rises” at times in her memory and is always with her.

Secondly, there is the “attentive, social self.” The attentive, social self is ordinary and normal, and we shouldn’t want it any other way. Pilots, surgeons, and ambulance drivers ought to be regular and ordinary. “You want him to approach and undertake his work with no more than a calm pleasure.” Please, captain, let’s not try any barrel rolls on our flight to Madrid.

Oliver doesn’t officially name the third self but refers to it as an “artist” or “dreamer.” Her comments on this third self have accompanied my thoughts over the past few days:

“In creative work—creative work of all kinds—those who are the world’s working artists are not trying to help the world go around, but forward” (emphasis original).

“This [third] self is out of love with the ordinary… [The] concern [of the extraordinary] is the edge, and the making of a form out of the formlessness that is beyond the edge.”

Education & The Edge

I find myself, as an educator, not necessarily out of love with the ordinary, but certainly in love with the edge. I would rather experiment in an attempt to move forward than be grounded in the ordinary, keeping things going ‘round. Making “form out of the formlessness that is beyond the edge” seems to be my regular pursuit.

To me, in education, what lives at the edge and in the domains beyond are ideas such as ungrading, radical student agency, and trust in the appeal of any subject for its own sake, stripped of scaffolds and extrinsic prodding. I love the work of weaving these intangible ideas into the world of my classroom.

This type of work, call it alchemy or distillation, this wrangling of theory into practice, is… difficult.

Allow me to now follow up on specific structural changes from the last report before shifting back into loftier thoughts.

Marking with 1-4s instead of Pass/Work on it.

Part of my new structure has been to provide marks on student work ranging from a 1 to a 4. A 4 signifies the student learned the thing or completed a thing in a way that met all criteria. Doing this forces me to sharpen my feedback. Also, students have mentioned they appreciate the more granular scale, as opposed to my last approach which gave them a binary “you did it” vs “keep working on it.”

All this said, I have found that this takes much more time than last semester’s structure. Giving feedback helps students practice and learn. This is good. Obviously, when they do more work, they return it to me. Thus I have more to review. Hello, Sisyphus. I need to reevalute what I provide granular feedback on and what I simply have them do and move on from.

Writing Tasks

I planned to give my students a writing task every two weeks. These tasks would aim at authentic writing opportunities. One every two weeks felt too frequent for my students, especially with everything else we’re doing. Even though we’re already four weeks into the term, I’ve only had students complete one task. Authentic writing is one of those formless ideals I’m struggling to make real in my classroom.

Grading Conferences

I started my in-person grade conferences today. I enjoyed chatting with each student but am unconvinced that the benefits of conferencing justify the time needed to make it happen. Each class will probably need 3 full days of students working independently while I’m in the hall conferencing. Is that too much?

Letters to Mr. Merrill

Every two weeks, students write a brief letter to me. I read and reply. So far, I’m fond of this plan. It helps me check up on each student regularly. I’m not sure if my students love the frequency, though. There was some grumbling when they “already” had to write another letter.

Focusing on Goals

Some of my students have really leaned into their personal goals. I have students sectioning off parts of their notebooks to write their thoughts on discographies they’re analyzing. It’s fun to see them excited about their plans. I want to find ways to have students share their good ideas with classmates.

Having class goals has been great. I’ve been more conscious to mention which mini goal any activity in class is helping us progress towards. Maybe the students notice a difference, maybe not. At the very least I hope they sense more rationale behind the things I ask them to do.

Conclusion

All in all, while I’m happy with the changes I’ve made, I find myself expended. I’m working later into the evening. I’m tired. I’m more disorganized and scattered. It could also be that my low-demand study hall “class” from last semester swapped out for my creative writing class this semester. I have more to plan and less time to do it.

Teaching is a profession of balancing, never a profession of balance.

Should I Seek the Extraordinary?

In all my experimenting I do wonder if I have the right to pursue the edge. On the scale of professions ranked from “should be ordinary” to “should be extraordinary,” where does teaching fit? Certainly, I want my doctors to do the regular, guaranteed-to-work stuff. I want bus drives to stay away from the edge, literally.

I think of the distinction between researchers and practitioners. While I want my doctors to do the regular stuff, I certainly want other medical researchers to pursue the edge. Please test it out and then pass the findings along to doctors that could help me one day.

We want innovators and dreamweavers in every domain, but when should they experiment elsewhere?

Sure, there are universities where professors research education, but the pass-down of information lags. Do I take matters into my own hands, experiment in my own class, or is that irresponsible because my current students need a successful education now? Experiment somewhere else, crazy teacher, just let us learn.

The consequences of my experimentation don’t affect me nearly as much as it affects my students. They’re who all of this for in the first place.

…

I don’t know. No answers; just thoughts. Thanks for reading. ✌️

If you have insights to share related to the topics I’ve discussed, I’d love to hear from you.

📼 My collection of videos to start class.

🖋️ Poems I share with my students.

🎹 My playlist of gentle music.

📚 What I’m reading/highlighting.

Brandon, thank you for sharing your practice. I also ride the line between theory and practice and experiment a lot inside of the classroom. I teach high school students. (I apologise that this comment ran a little long.)

It sounds like you're trying several different things but running into time and effort constraints. One approach to this which has worked well for me is to reduce the scope of my activities. In my writing class, none of my assignments are ever more than a page. This constraint forces revision while still allowing for creativity, and limits my workload for marking/feedback. Do the same things but do less of it. Maybe, rather than a letter, students design Notes for you (like in Substack but in your own software); one developed thought, rather than a letter.

Not all work needs to be submitted. Create some tension between work that is submitted, and therefor receives feedback, and that which is only intended for practicing new concepts.

Student conferences may happen once or twice a term but they are a huge investment of time to be out of the classroom. Much of the feedback is common across students. If you provide good written feedback, and then walk through examples of common mistakes with the whole class, then you arrive at the same point much more quickly. With a quick question for students of concern during breaks (for example), 'What did you think of my written feedback', I can see if they've taken it in. Most of the problems from feedback isn't that they don't understand, but that they don't read it.

For grading, all my assignments are out of 10, regardless of the task, except end-of-term submissions are worth 15. In part, this is to detach marks from perceived importance. As the only marks awarded are from submitted work, there are no fuzzy marking assessments for 'behaviour' and other intangibles. Good behaviour is a minimum expectation. My submission rate is close to 100%, without applying force.

Should you experiment? Yes, you must; the alternative is mind-numbing senselessness. When you experiment, you should optimise for both yourself and your students effort, where your life should get much easier and your students' experiences should feel more fun. I always try to, 'Do less but make it mean more'.

I like hearing about your experiments! Something I miss about teaching high school is being able to structure my class around repeating weekly patterns. By contrast, middle school is all play by ear and adjusting day to day.